Axolotls may refuse food for many different reasons. Here is a list of 10 possible causes, ranked from most common to least common. Try working your way down the list, ruling out the more common issues until you can identify the problem you’re dealing with.

1. Moving stress

It’s not uncommon for axolotls to refuse food for a day or two when they first arrive in a new home. Keep in mind, s/he is trying to adjust to a whole new environment, including a new owner, and possibly different foods and feeding methods. Be patient! Your new pet will warm up to you once s/he realizes that there is nothing to be afraid of.

2. Warm water

Axolotls are subtropical, and do not handle summer temperatures well. Most axolotls suffer from heat stress and will refuse food as their water reaches 23°C or higher. Heat stress in axolotls can be deadly, particularly at 24°C or above. In an emergency, fans or frozen water bottles can help shave off a few degrees. I will post a more in-depth article on this topic as soon as I am able. Thank you for your patience.

3. Ammonia issues

Ammonia makes axolotls queasy, so they may refuse food or even throw up. If you’re keeping your axolotl in a tank, make sure your filter is properly cycled. In a tub, remember to do a full water change every day!

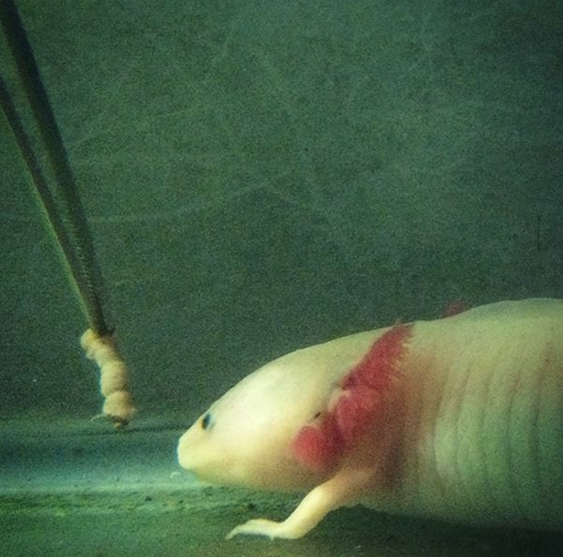

4. Problems with the food

Axolotls may ignore or spit food out when it’s too big, too hard, or it just has a nasty taste. Try cutting overlarge food in half. You can use scissors to cut up large earthworms, or a pill cutter to cut overlage pellets. Choose a pellet that softens rapidly in water. Avoid worms that taste bitter, such as red wigglers (Eisenia fetida). To avoid spoilage, don’t buy larger quantities of dry food than your axolotl can consume in approximately one month, and try to reseal the package properly after use. Don’t allow frozen food to thaw and then re-freeze.

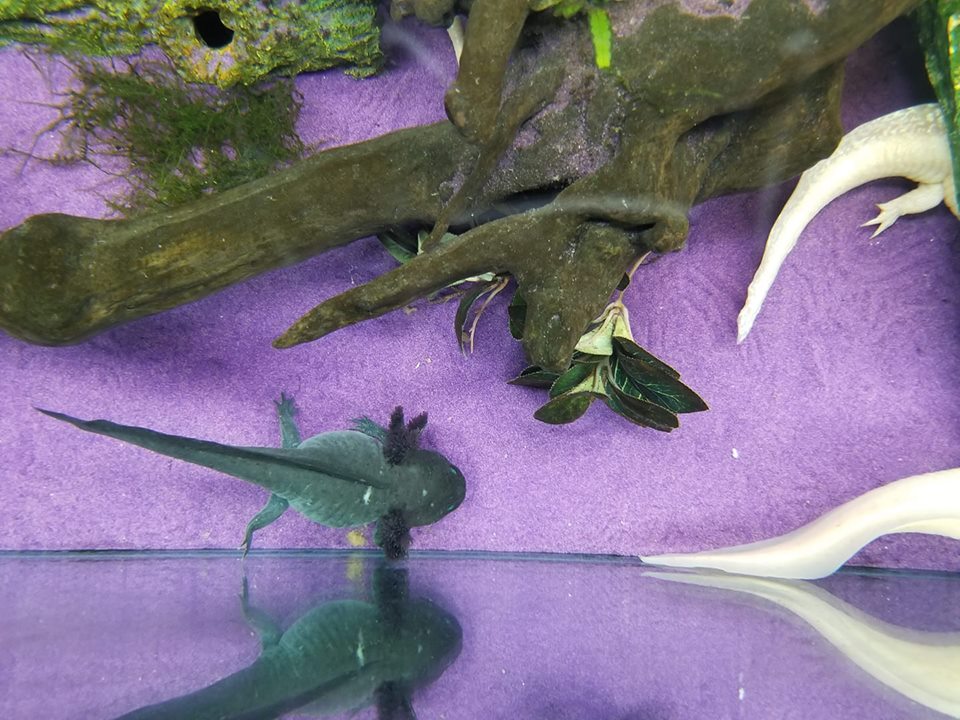

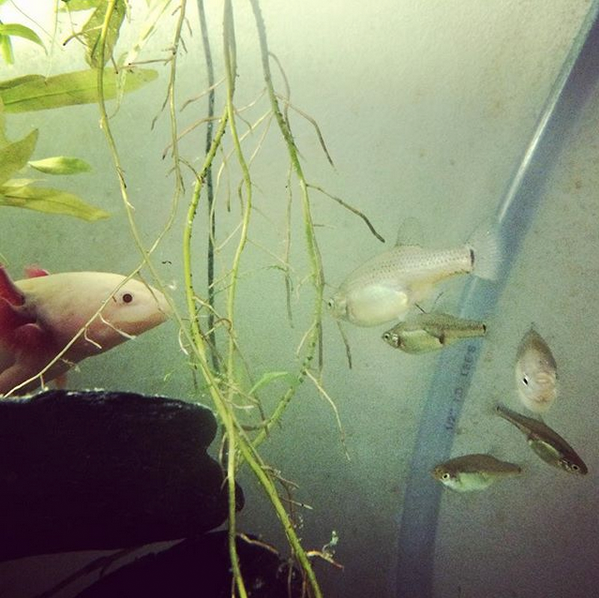

5. Aggressive tankmates

If your axolotl is moving away from food or staying hidden at feeding times, they may be afraid that moving towards the food will draw in their neighbor’s wrath — especially if they’ve gotten nipped by them before. The solution is to feed the more aggressive axolotl in a separate container. If you’re worried about nipping at other times, it’s best to rehome the aggressive axolotl to another tank entirely. Note that biting of same-sized tankmates is not a normal adult behavior and often indicates a severe nutritional deficiency.

6. Pre-hibernation

In very cold water (<15°C), axolotls may act sluggish and show a lack of interest in food. They may also poop more than usual, and/or vomit, especially at the lowest end of their tolerated temperature range (4-8°C) or after a rapid decrease in temperatures (e.g when fridging). This is a normal physical adaptation to the low temperatures, and not a sign that your axolotl is sick. Gradually increase temperatures to a more comfortable range (15°C-18°C) and your axolotl should resume their normal behaviour.

7. Impaction

If your axolotl refuses to eat for several days in a row, they could have swallowed something that caused a blockage. This is unfortunately a relatively common issue in axolotls, as they have a tendency to eat aquarium gravel, small rocks and anything else they can fit in their mouths. I will be writing a separate article on how to treat and diagnose impaction, but in the meantime, please consult a veterinarian if you suspect that your axolotl is impacted. If your axolotl swallowed a piece of Indian almond leaf, please inform a vet immediately, as this also poses a risk of tannin overdose.

8. Intestinal parasites

If your axolotl has been refusing food and/or throwing up for a week or longer, and all of the above causes have been ruled out, intestinal parasites are the most likely culprit. You should contact a veterinarian in your area to discuss possible treatments. If you’re able to collect a stool sample, that will make parasite identification a lot easier. Your vet may also ask for a water sample.

9. Egg or water retention

Egg and/or water retention rarely happens, but it does happen! In addition to causing discomfort, severe bloating compresses the animal’s digestive tract, making eating difficult. If your axolotl looks bloated and the above causes have been ruled out, try housing them in a 40% concentration of Holtfreter’s or John’s solution [more info on this soon]. If your axolotl is female, try pairing her with a male to trigger egg-laying, and add some plants or decor for the eggs to be deposited onto. Contact a veterinarian asap if:

- you see no improvement after 48 hours

- other symptoms are present

- your female seems to be having difficulty laying eggs, or the eggs are looking non-viable

10. Other severe illness

If all the other causes have been ruled out, you should assume that your axolotl is battling a severe illness and requires urgent veterinary care.